Which Ending of Mark’s Gospel is Correct?

By Shawn Nelson

March 2017

There are four possible endings for Mark’s gospel. Which ending is authentic?

This paper was in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the course titled New Testament Survey I (NT510) taken at Veritas International University in March, 2017.

Copyright © 2018 Shawn Nelson.

Overview

There are four possible endings for Mark’s gospel. Which ending is authentic? Two of these, the Freer Logion and the Shorter Ending (SE), find no support and can be eliminated. When external evidence is analyzed there is greater numerical support for the Longer Ending (LE), but the LE is missing from the earliest and most reliable manuscripts. Arguments given for the LE based on internal evidence include: (1) it is the more difficult reading (and therefore correct); (2) it provides better structural harmony; (3) it presents proper closure; (4) there may be evidence that Mark added the LE later (in which case multiple versions of Mark would have been in circulation); and (5) it is possible a colleague added the LE after Mark’s death or imprisonment (and it can still be rightly considered canonical). Regardless, the majority of scholars reject the LE for one or more of the following reasons: (1) the LE is not consistent in vocabulary and style; (2) the original ending could have been lost; (3) Mark may have planned to write a sequel but was prevented; (4) good explanations exist for why Mark might have intentionally brought gospel to an abrupt end at v. 8. Other examples from antiquity can be found with books ending in a similar, abrupt manner and a sudden ending is consistent with the rest of Mark. This type of ending was likely a literary tool used by Mark to evoke a response from the reader.

A Popular Topic Today

The problem of Mark’s ending has been widely discussed in recent years.[1] It has been called “a flash-point in NT criticism,”[2] “the greatest of all literary mysteries”[3] and even “the chief textual problem in… the New Testament itself.”[4] A series of recent conferences has propelled the topic further into the academic spotlight.[5] There is a wealth of material available on the subject. This short paper provides a summary of the various modern views while answering the question of why the majority of scholars continue to place the closing of the gospel at v. 8.

The Four Endings of Mark

There are four extant endings to Mark’s Gospel.

Longer Ending (LE). First, there is the Longer Ending (commonly abbreviated as “LE”). This is the Mark 16:9-20 which continues to be printed in most English Bibles. This ending contains very brief descriptions of a final appearance of Jesus (vv. 9-13), an abbreviated version of the Great Commission (vv. 14-16), and Jesus’ ascension and the gospel’s advancement throughout the world (vv. 20).[6] There is also a mention that signs would accompany believers such as casting out demons, tongues, handling venomous snakes and drinking poison (vv. 17-18).

Freer Logion. Second, there is an expanded, longer ending called the “Freer Logion.” It contains the entire LE above but also inserts the following after verse 14:

And they excused themselves, saying, “This age of lawlessness and unbelief is under Satan, who does not allow the truth and power of God to prevail over the unclean things of the spirits [or, does not allow what lies under the unclean spirits to understand the truth and power of God]. Therefore reveal your righteousness now”—thus they spoke to Christ. And Christ replied to them, “The term of years of Satan’s power has been fulfilled, but other terrible things draw near. And for those who have sinned I was handed over to death, that they may return to the truth and sin no more, in order that they may inherit the spiritual and incorruptible glory of righteousness that is in heaven.”[7]

Shorter Ending (SE). Third, there is a “Shorter Ending” (abbreviated as “SE”). With this ending the only text found beyond v. 8 is:

And all that had been commanded them they told briefly to those around Peter. And afterward Jesus himself sent out through them, from east to west, the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation. Amen.[8]

Abrupt Ending. Lastly, there is the view that v. 8 is the end of his gospel whether Mark intended it or not. This view holds to an abrupt end with the statement: “So they went out and fled from the tomb, for terror and amazement had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid” (Mk. 16:8, NRSV).

Role of Textual Criticism

How do scholars attempt to determine which ending is the original? Attempting to determine the original wording of a text is the practice of textual criticism. Textual critics rely on both external and internal evidence to form probabilistic conclusions.

There are three kinds of external evidence: (1) chronological, (2) geographical and (3) genealogical.[9] Generally speaking, earlier manuscripts are preferred to older (this is called chronological evidence). Stronger weight is given to more widely distributed manuscripts which are in agreement as opposed to those in closer proximity (geographical evidence). Evidence is not based on mere number of manuscripts alone but a manuscript’s text type must also be considered (genealogical evidence).[10] Of the four major text types (Alexandrian, Caesarean, Western and Byzantine) the Alexandrian is considered most reliable.[11] But a reading in two other text types (such as an agreement in the Western and Byzantine) could outweigh a single Alexandrian reading.

There are also two types of internal evidence: (1) transcriptional and (2) intrinsic.[12] Transcriptional evidence analyzes transmission by the copyists. It is an attempt to determine the original reading based on known habits and traditions of the scribes, viz.: scribes tended to improve rough readings (hence less-refined grammatical constructions are preferred); scribes were less likely to remove words and phrases as they were to clarify them (hence shorter readings are also preferred). The second kind of internal evidence is intrinsic evidence. Intrinsic evidence analyzes stylistic features like vocabulary and phraseology. Are the words consistent with rest of the work? Does the reading contain consistent theology—i.e., is it first consistent with theology of book/letter, then author’s theology, then all of NT and entire Bible? Are there smooth transitions leading into the text in question? Does the text fit the immediate context? Finally, is there anything that might have motivated a scribe to add or change the text?[13]

Gleason Archer combines many of the external and internal principles of textual criticism into the following guide: “The preferred reading is the one that: (1) is older; (2) is more difficult; (3) is shorter; (4) best explains variants; (5) has the widest geographical support; (6) conforms to the style and diction of the author; and (7) reflects no doctrinal bias.”[14]

Eliminating Two Endings from the Start

Two of the four endings can be eliminated because of near-unanimous rejection.

Rejection of the Freer Logion. There is no scholarly support today in favor of the Freer Logion being the original. Its only support comes from a single 4th century Greek manuscript and a mention by the church Father Jerome.[15] Its external evidence is entirely underwhelming, it contains non-Markan vocabulary and has “an unmistakable apocryphal flavor.”[16]

Rejection of the SE. There is also a near unanimous rejection of the Shorter Ending.[17] “Hardly anyone has supposed that this ‘Ending’ is genuine; it is too obviously an ad hoc fabrication.”[18] It is regarded to be “textually spurious” by almost all scholars.[19]

The rejection of both endings is “almost a universally held conclusion.”[20] Therefore, the debate over which ending is correct can rightly be narrowed down to the Longer Ending and the Abrupt Ending views.

Weighing the External Evidence

Which ending does the external evidence favor? There are more manuscripts for the Longer Ending (see Figure 1); yet it is argued that the majority are late and from an inferior textual tradition. Most scholars (see Figure 3) conclude the evidence favors an end at v. 8.

External Evidence for the LE. The first clear witness to this ending comes from Irenaeus (2nd century AD).[21] Justin Martyr (ca. AD 153) and Tertullian (AD 150-225) may also have shown familiarity with the LE.[22] However, its strongest support comes from the sheer number of manuscripts containing this version: it has been estimated that the Longer Ending has ninety-five percent of Greek manuscript attestation;[23] this can be increased to ninety-nine percent when other forms of attestation are included.[24] As remarkable as this is, the raw numbers “can be quite deceiving.”[25] Metzger explains:

The longer ending (vv 9-20) is clearly the most attested reading. It is validated by almost all of the extant Greek manuscripts, a significant number of minuscules, numerous versions, and scores of church Fathers. Geographically it is represented by the Byzantine, Alexandrian, and Western text types. However, one should be careful not to reduce textual criticism into an exercise of manuscript counting. Though the longer ending is widely attested, the vast bulk of manuscripts are from the generally inferior, Byzantine text type dating from the 8th to the 13th centuries…[26]

External Evidence for Abrupt Ending. The strongest externally-based argument against the LE is that it is missing from the earliest and most reliable manuscripts (again, see Figure 1). Codex Sinaiticus (ℵ, 4th/5th century AD) and Vaticanus (B, 4th century AD)—which are both from the Alexandrian text type and are considered more reliable—do not have vv. 16:9-20. It is also omitted from many early translations into ancient Latin, Syriac, Armenian, Ethiopic and Georgian.[27] While a few early church fathers arguably make allusions to the Longer Ending, there is a notable lack of witness from many other prominent ones, viz., Clement of Alexandria, Origin, Cyrian, Cyril of Jerusalem.[28] Eusebius and Jerome both said the passage was missing from nearly all Greek copies available to them.[29] Lastly, there are many manuscripts that are physically marked with asterisks or obeli which would typically indicate the section was a spurious addition.[30]

Weighing the Internal Evidence

Scholars are tasked with combining the external evidence above with internal evidence to form an opinion about the most probable scenario. All of the major arguments based on internal evidence are summarized below.

Internal Evidence for the Longer Ending

Argument from the principles of textual criticism. William Farmer is considered a leading advocate for the Longer Ending. Farmer argues that the Longer Ending must be the original because it is the more difficult reading.[31] The basis for this argument is that “textual criticism is governed by one overriding principle (i.e., choose the reading which best explains the rise of the others) and two sub-canons (i.e., the more difficult and shorter reading is preferred).”[32] Given the choice between the Abrupt Ending and the LE, certainly the LE is the more difficult reading (i.e., it mentions handling snakes and drinking deadly poison).

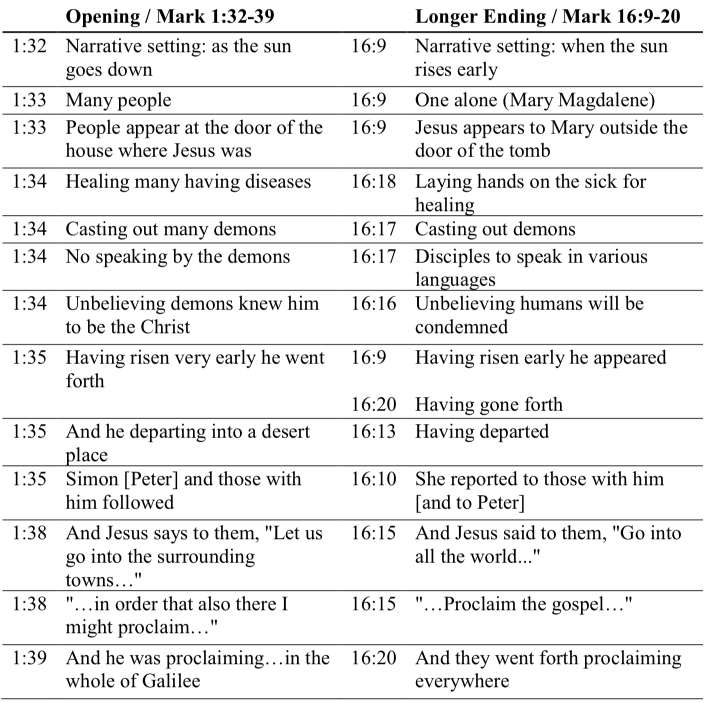

Argument from structural harmony. Maurice Robinson (Perspectives of the Ending of Mark) is another advocate for the Longer Ending. Robinson argues that the LE is most consistent with the opening of Mark’s gospel. “A correspondence exists between the ‘Son of God’ theme at the beginning of Mark and the ascension/enthronement motif that concludes the LE.”[33] He also sees conceptual and verbal parallels between the LE and the rest of Mark. Among his examples are the chiastic-like parallels and contrasts between the LE and the opening of Mark (see Figure 2). Though too long to include here in detail, he finds many other parallels between the LE and throughout Mark 3, 6, 7-8.[34] Most notable among the latter are the contrasts between the disciples’ first commissioning (Mark 3:14-15) and the disciples’ final commissioning within the LE.

These parallels should be considered in light of their cumulative effect as they might bear upon the authenticity of the LE. Certainly such parallels are more than coincidental: they reflect existing structural and thematic elements that appear throughout canonical Mark, and which find their culmination in the LE.[35]

Argument from proper closure. Quite simply put, Mark’s gospel would be incomplete without a proper ending. If the Long Ending is inauthentic then Mark comes to a surprising end at v. 8. This ending would read: “So they went out quickly and fled from the tomb, for they trembled and were amazed. And they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.” The last two words of Mark would be “ἐφοβοῦντο γάρ” or “they were afraid for.” J. R. Harris argued that ending with the word “for” (γάρ) presents grammatical and literary problems: it would “not [be] a literary ending, not a Christian ending, and can hardly be a Greek ending.”[36] From a literary perspective, the sudden break in the narrative is anti-climactic and creates an “intolerable discontinuity in the narrative and in the readerly expectations created by it.”[37] Robinson adds that any ending which fails to demonstrate the complete fulfillment of Jesus’ resurrection prophecies “would be destructive of Markan style and purpose.”[38] For opponents, these arguments are met with satisfactory explanations below.

Argument that there existed two versions of Mark. A theory championed by William Farmer and David Black makes an assertion that there was a private and then a final version of Mark’s gospel. Eusebius (263-339 AD) gave insight that the content of Mark’s gospel came from the teaching discourses of Peter:

The Gospel according to Mark had this occasion. As Peter had preached the Word publicly at Rome, and declared the Gospel by the Spirit, many who were present requested that Mark, who had followed him for a long time and remembered his sayings, should write them out. And having composed the Gospel he gave it to those who had requested it.[39]

In other words, Mark was circulating a private copy of his gospel to those who asked him. This would have been while Peter was alive because Eusebius added, “When Peter learned of this, he neither directly forbade nor encouraged it.”[40] Following Peter’s death, after he founded the church of Alexandria, as a memorial to Peter, Mark may have abridged the ending to conclude the story.[41] Another version of this theory is that it was not Mark himself who abridged his gospel, but he may have been prevented by death or persecution from completing his gospel. A colleague of Mark could have appended Mark’s ending with his notes.[42] Either way, a version of Mark with and without the LE would have been in circulation simultaneously. Under these theories both versions would have been written by Mark.

Argument for canonicity despite being non-Markan. David Warren, David Hester and Maurice Robinson argue that the LE is canonical whether or not it was written by Mark. There are examples of Old Testament books which were finished by others after the author had died, viz., Joshua completing Deuteronomy for Moses, Eleazar and Phinehas completing Joshua after his death and Gad and Nathan completing both books of Samuel after his death.[43] All of these Old Testament books are considered canonical despite these posthumous additions.

Majority of Scholarship Rejects the Longer Ending

The majority of scholars reject the LE despite the evidence presented above (see Figure 3).[44] Most assert that Mark’s gospel ends at v. 8 for one or more of the following reasons.

Internal Evidence for the Abrupt Ending

Argument that Longer Ending is non-Markan. The biggest obstacle to acceptance of the LE is that it is not consistent in vocabulary, style and practice. Eighteen terms are found nowhere else in Mark’s gospel.[45] Absent are some of Mark’s most frequently used words (e.g., “immediately” or “again”).[46] There is a very obvious awkward transition between vv. 8 and 9;[47] Mary is curiously reintroduced again in v. 9 just a few verses away from her first introduction in v. 1—while the other women are left out.[48] There is also alarming mention of handling venomous snakes and drinking deadly poison which seems to be inconsistent with the rest of Scripture.[49] While Terry provides good counter arguments to most of these points, as already mentioned, he is clearly in the minority.[50]

Argument that Mark’s ending was lost (abrupt ending was not intended). There is the theory from J. K. Elliott and Robert Stein that Mark originally had a longer ending but this was somehow lost. Similar to a theory above, he could have been unable to finish his gospel due to natural death, martyrdom, imprisonment, etc. The difference here is that there would have been a very narrow window of time just after Mark began circulating his gospel where—if he and those familiar with the text were killed—the ending could have been lost without the early Church’s awareness.[51] This would mean Mark’s inspired ending is missing with the extant text ending at v. 8—a conclusion some would certainly find difficult to accept.[52] This view is considered weak since it is “purely conjecture and lacks any concrete evidence”[53] and “source criticism suggests that neither Matthew nor Luke possessed copies of Mark extending beyond 16:8.”[54] There is also reason to believe Mark was written on a scroll and it is not likely the ending of a scroll would be lost.[55]

Argument that Mark intended to write a sequel. There is a theory that Mark may have intended to write a second part to his gospel. This sequel was either never achieved or, more likely, his material become incorporated into the book of Acts. Bruce mentions four scholars holding the latter view: Weiss, Feine, Blass, Clarke;[56] he himself finds it highly improbable since no mention of this is made in the historical tradition.[57]

Argument Mark was deliberately brought to an abrupt end. Finally, there is the view championed by Bruce, Metzger and Stonehouse which is the widely held conclusion by scholars today that Mark intentionally ended his gospel at v. 8.[58] Those holding this position have much explaining to do regarding why Mark would conclude his ending in such a strange manner. This challenge will be met in the next section.

How to Explain an Intentional Ending at v. 8

Ending in γάρ is not unprecedented. As explained previously, if Mark’s ending is placed at v.8 then the last words of his gospel are “they were afraid for” (ἐφοβοῦντο γάρ). The word “for” (γάρ) was once considered an invalid ending for a book. However, there are examples of other sentences ending in “for” (γάρ) in the Bible. John 13:13 says, “You call Me Teacher and Lord, and you say well, for so I am” (εἰμὶ γάρ). And the first sentence in Gen. 18:15 in the LXX reads, “for she [Sarah] was afraid” (ἐφοβήθη γάρ).[59] Despite clear parallels from Scripture, some scholars continued to insist that a sentence or paragraph ending with γάρ was different from an entire book ending this way.[60] It was then discovered that Plotinus had in fact ended one of his books with the same word.[61] The conclusion today is that, while strange, there are sufficient examples “to show that from the philological and literary viewpoint ‘ἐφοβοῦντο γάρ’ is a perfectly possible ending.”[62]

Abrupt endings were not unprecedented. J. L. Magness has demonstrated that abrupt endings can be found in other ancient Greek, Roman and Hebrew writings.[63] There are other examples of abrupt endings in Scripture, such as the book of Jonah ending with a question being asked to a pouting prophet to which no answer is provided.[64] Such “abrupt conclusions were accepted and understood by ancient writers and readers.”[65]

Abrupt end consistent with rest of Mark. Bruce, Strauss and Iverson see an abrupt end befitting Markan style. It is argued that an abrupt ending is consistent Mark’s abrupt beginning in chapter one.[66] There is a sense of mystery and awe running through Mark’s entire gospel which makes it fitting that the ending should continue with mystery.[67] Fear is the normal response to a miraculous event throughout Mark’s gospel. Some suggest the women’s fear is actually a positive reaction to the angel’s announcement of “He is risen! He is not here” (v. 6).[68] Others see blatant disobedience in that they “said nothing to anyone” (v. 8) when commanded to “go, tell” (v. 7)—but this too would be consistent with Mark.

The angelic command at the tomb was met with complete disobedience by the women. Jesus was left jilted in Galilee, the twelve were never informed of the resurrection, never restored to service, and never received apostolic commissioning.; Thus it is argued that the women’s response in 16:8 is a tragic, disastrous conclusion to Mark’s Gospel.[69]

Yet as tragic as this type of ending is, it is consistent with Mark’s unusually harsh characterization of Jesus’ followers.[70]

Ending not as strange as we would think. Bruce suggested that a first century reader of Mark’s gospel would not think the ending is as strange as the modern 21st century reader. Modern readers place great value on the post-resurrection appearances of Jesus as evidence of his resurrection. However, there is evidence to suggest that the story of the empty tomb played a more important apologetical role in proving the resurrection for primitive Christians.[71] The prominence of the empty tomb can be found in the fact that it is emphasized in all four gospels as well in the early Apostolic Preaching.[72] It can also be seen in the order given by the disbelieving elders to say that the disciples stole his body (Mt. 28:12-15). With this in mind the early church might have found the abrupt ending much more palpable than readers today.

A literary tool intended to elicit a response from the reader. If Mark deliberately brought his gospel to an end what could have been his motivation? The most obvious and widely accepted answer is that an abrupt end is an attempt to force the reader into response. Strauss beautifully summarizes this view:

Like the characters in the narrative, the reader must decide how to respond to this proclamation—with faith or with rejection… The narrator rather leaves the readers with the proclamation of the resurrection and an implicit call to decision. Will they, like Jesus, face suffering and trials with faithfulness, or will they flee and deny him like the disciples? Will they respond to Jesus’ suffering with recognition and faith, like the centurion, or with unbelief and rejection, like the religious leaders? The resolution (or perhaps irresolution) of the plot calls the reader to decision.[73]

In short, the stunning ending could very well be strategically designed by Mark to elicit a response from the reader much like an unexpected movie ending might more familiarly do for us today. Among the mystery of Mark’s gospel—and most notably here the mystery of his final chapter—we may very likely find an invitation to enter into the story. This conclusion is sure to appeal to modern readers.

Conclusion

The majority of scholars put the ending of Mark’s gospel at v. 8. When external evidence is analyzed there is greater numerical support for the Longer Ending, but the LE is missing from the earliest and most reliable manuscripts. The biggest obstacle to acceptance of the LE is that it is not consistent in vocabulary, style and practice. Therefore the majority of scholars reject it. The abrupt ending at v.8 presents additional challenges. Yet, there are valid reasons why Mark might have been prevented from finishing his gospel such as imprisonment or death. But there is also the belief that Mark had reason to end his Gospel abruptly, and this is in keeping with his style. If true, Mark’s intention was to invite his readers into the story, a heart-felt invitation which extends to the reader today.

Postscript: Why Is This Relevant Today?

First-time readers of Mark’s Gospel are often confused over its bizarre ending. Evidence of genuine Christianity is said to include the handling deadly snakes and drinking poison (Mark 16:18). In most Bibles, this bizarre ending in accompanied with a footnote indicating that the most authoritative manuscripts omit Mark 16:9-20. While comforting to some, for others this footnote raises more questions: How exactly did a different ending end up in one of the Gospels? What does this say about the rest of Mark—or the entire New Testament? Can we really trust our Bibles or has the text been drastically changed along the way?

This paper has shown that there is good reason to believe that Mark’s gospel ends at v. 8, and therefore the strange practices mentioned in v. 18 are not binding upon Christians today. But even if the LE were authentic these practices can find complete fulfillment in the events of Scripture by the apostles.[74] Regardless of which position is held on the ending of Mark, it is important to point out that one’s view here does not severely impact one’s faith. “There is no central teaching of the Christian faith at stake in which view is chosen.”[75] Furthermore, this entire exercise is a practical introduction to the area of NT textual criticism. The tracing through the external and internal evidence for and against the LE prepares one with the skills needed to make similar decisions over other (much smaller) variants in the NT.

In short, Christians today can take comfort in the fact that no variant (in Mark or elsewhere in the NT) is significant enough to affect any central Christian teaching. There is no theological conflict here, no textual dilemma, and hence, no need for the modern Christian to doubt their Scriptures.

Figure 1. Textual Witnesses for Each Ending of Mark.[76]

No Ending—Texts that omit vv. 9-20:

ℵ(4th/5th AD), B (4th), 304, syrs (3rd/4th), copsams (3rd), armmss, codd (5th), geo1 (897), geoA (913), Clement of Alexandria (d.215), Origen (d.251), Eusebius mss (d.339), Epiphanus1/2, Hesychius mssacc. to Severus (d.450), Jerome mss (d.419), Ammonius, 2386missing page, 1420missing page.

Longer Ending—Texts that include vv. 9-20:

A (5th AD) , C (5th), D (5th), E (8th), G (9th), H (9th), K, M, S, U, W (w/ v.14 addition, 4th/5th), X, Y, Γ, Δ (9th), Θ (9th), Π, Σ (6th), Φ, Ω, 47, 55, 211, f13 (1013-15th), 28 (11th), 33 (9th), 157 (c.1122), 180 (12th), 565 (9th), 597 (13th), 700 (11th), 892 (9th), 1006 (11th), 1009, 1010 (12th), 1071 (12th), 1079, 1195, 1230, 1241 (12th), 1242, 1243 (11th), 1253, 1292 (13th), 1342 (13th/14th), 1344, 1365, 1424 (14th/15th), 1505 (12th), 1546, 1646, 2148, 2174, 2427 (14th?), Lect 60, 69, 70, 185, 547, 833, itaur, o (7th), itc (12th/13th), itdsupp, ff2, n (5th), itl (8th), itq (6th/7th), vg (4th/5th), syrc (3rd/4th), syrp (401-50), syrh (616), syrpal (6th), copbo, fay (3rd), armmss (5th), ethpp (16th), geoB (10th), slav (slav ms add only16:9-11, 9th), goth, Clement of Rome (c.95), Justindub (d.165), Diatessaron (c.170), Irenaeuslat mssacc. to Eusebius (2nd), Aphraates, Asteriusvid (d.341), Tertullian, Eusebius (d.339), Apostolic Constitutions (c.380), Didymusdub (398), Hippolytus, Ephiphanus1/2 (403), Marinusacc. to Eusebius, Marcus-Eremita (d.430), Severian (d.408), Nestorius mssacc. to Severus (d.451), Rebaptism (258), Severus (d.420), Ambrose mssacc. to Jerome (d.397), Augustine (d.430).

Add’l Longer Ending—Texts that include vv. 9-20 with critical note or sign:

f1 (948-14th AD), 137, 138, 205 (15th), 1110, 1210, 1215, 1216, 1217, 1221, 1241vid, 1582, WH (19th).

Longer and Shorter Endings—Texts that include shorter ending and vv. 9-20:

L (8th AD), Ψ (9th/10th), 83 (6th/7th), 99 (7th), 112 (6th/7th), 274mg (5th), 579 (13th), l (1602), syrhmg (616), copsamss (3rd), copbomss (3rd), ethmss,TH (500).

Shorter Ending—Texts that only include shorter ending:

ita (4th AD), itk (4th/5th).

Figure 2. Parallels and Contrasts Between the Opening of Mark and the Longer Ending.[77]

Figure 3. Scholarly Conclusions Regarding Mark’s Ending.

Scholars in Favor of the Longer Ending; Mark 16:9-20 is Authentic:

Black, David Alan (1952-)

Burgon, John W. (1813-1888)

Farmer, William R. (1921-2000)

Hester, David W.[78]

Robinson, Maurice A. (1947-)

Terry, Bruce

Scholars Rejecting the Longer Ending; Mark 16:8 is the End (Intended or Not):

Bock, Darrell (1953-)

Bruce, F. F. (1910-1990)

Carson, D.A. (1946-)

deSilva, David A. (1967-)

Elliott, J. K.

Evans, Craig A. (1952-)

Fee, Gordon (1934-)

Geisler, Norman L. (1932-)

Gundry, Robert H. (1932-)

Guthrie, Donald (1916-1992)

Hooker, Morna D. (1931-)

Hort, Fenton J. A. (1828-1892)

Iverson, Kelly

Kelhoffer, James A. (1970-)

Kruger, Michael J.

Lightfoot, R. H. (1883-1953)

Marxsen, Willi (1919-1993)

McDonald, Lee Martin

Metzger, Bruce M. (1914-2007)[79]

Moo, Douglas J. (1950-)

Nix, William E.

Porter, Stanley E. (1956-)[80]

Schweizer, Eduard (1913-2006)

Stein, Robert H. (1935-)

Stonehouse, N.B. (1902-1962)

Strauss, Mark

United Bible Societies Committee

Wallace, Daniel B. (1952-)

Wellhausen, Julius (1844-1918)

Westcott, Brooke Foss (1825-1901)

Footnotes

- Robert H. Stein, “The Ending of Mark,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 18, no. 1 (2008): 79. ↑

- Maurice Robinson et al., Perspectives On the Ending of Mark: Four Views, ed. David Alan Black (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2008), Kindle loc. 1167-1169. ↑

- D E Nineham, The Gospel of St Mark (London: Penguin Books, 1963), 439. ↑

- A. T. Robertson, Studies in Mark’s Gospel, (New York: Macmillan, 1919), 129. ↑

- The Evangelical Theological Society Southwestern Regional Conference made the ending of Mark a conference topic in April, 2001. Following its popularity, another conference was held April 13-14, 2007 at Southeastern Seminary titled “The Last Twelve Verses of Mark: Original or Not.” One-hundred and fifty New Testament students and scholars from many parts of North America and Europe travelled to hear a formal discussion on the question of the originality of Mark’s ending with scholars presenting their cases for each view. Presentation papers were later published in the book Perspectives On the Ending of Mark: Four Views. Daniel B. Wallace argued that Mark intended his Gospel to end at 16:8; Maurice A. Robinson argued that Mark 16:9–20 is original; J. K. Elliott argued that the original ending of Mark was lost; Black argued that Mark 16:9–20 was added by Mark to round off Peter’s lectures. See Perspectives, Kindle locations 73-105. ↑

- Robert G. Bratcher and Eugene A. Nida, A Handbook On the Gospel of Mark. UBS Handbooks; Helps for Translators Series (New York: United Bible Societies, 1993), 506. ↑

- Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary On the Greek New Testament, 2nd ed. (London; New York: United Bible Societies, 1994), 104. ↑

- Stein, 81. ↑

- Norman Geisler and William E. Nix, A General Introduction to the Bible, Rev. ed. (Chicago: Moody Publishers, 1986), 476. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Craig A. Evans and Stanley E. Porter Jr., eds., Dictionary of New Testament Background (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2000), 673. ↑

- Geisler and Nix, 476. ↑

- Ibid., 477-478. ↑

- Gleason Archer Jr., A Survey of Old Testament Introduction, 3rd ed. (Chicago: Moody Press, 1994), 64. ↑

- Metzger, A Textual Commentary On the Greek New Testament, 104. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Vincent Taylor, ed., The Gospel According to St Mark, 2nd ed. (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1966), 610. ↑

- Bruce, F.F. Bruce, “The End of the Second Gospel,” The Evangelical Quarterly 17 (1945): 178. ↑

- Craig A. Evans, Mark 8:27-16:20, Volume 34b (Word Biblical Commentary), Revised ed., ed. Bruce M. Metzger, David Allen Hubbard, and Glenn W. Barker (Chicago: Zondervan, 2015), 545. ↑

- Taylor, 610. ↑

- Metzger, A Textual Commentary, 103-104. ↑

- This is disputed. Stein argues that Tertullian did not reference the Longer Ending while Hester argues that at least four of Tertullian’s writings make allusions to 16:9-20. Metzger says “It is not certain whether Justin Martyr was acquainted with the passage.” See Stein, “The Ending of Mark,” 82; David W. Hester, Does Mark 16:9-20 Belong in the New Testament? (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2015), 122; and Metzger, A Textual Commentary, 103-104. ↑

- Michael W. Holmes, “The Many Endings of the Gospel of Mark,” BRev 17, no. 4 (2001): 19 in Stein, 82. ↑

- Kurt & Barbara Aland, Text of the New Testament: an Introduction to the Critical Editions and the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, Revised and Enlarged (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989), 292 in Stein, 82. ↑

- Perspectives, Kindle location 242. ↑

- Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 3rd ed. (New York: Oxford University, 1992), 293 in Kelly R. Iverson, “Irony in the End: A Textual and Literary Analysis of Mark 16:8,” The Biblical Studies Foundation, May 2001, 1-2. ↑

- Bratcher and Nida, A Handbook On the Gospel of Mark, 506. ↑

- Stein, 82. ↑

- Metzger, A Textual Commentary, 103-104. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Iverson, 3. ↑

- Michael W. Holmes in Scot McKnight, ed., Guides to New Testament Exegesis, vol. 1, Introducing New Testament Interpretation (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 1989), 56. ↑

- Robinson in Perspectives, Kindle location 1630. ↑

- Ibid., 1568. ↑

- Ibid., 1571-1573. ↑

- J. Rendel Harris, Side-Lights On New Testament Research (London: James Clarke & Co., 1908), 87. ↑

- Norman R. Petersen, “When Is the End Not the End? Literary Reflections On the Ending of Mark’s Narrative,” Int 34, no. 2 (1980): 154. ↑

- Perspectives, 1634-1636. ↑

- The Church History of Eusebius 6.14.6 in Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, eds., Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (Christian Literature Company: New York, 1890), 261. ↑

- Eusebius 6.14.7. ↑

- Perspectives, Kindle locations 2924-2930. ↑

- Hester, 152. ↑

- David H. Warren in foreword to Hester, ix. ↑

- Hester has seventy-six pages (nearly half his book) covering the historical development of the debate from 1800s to the present day. “From the late 1800s to the late 1950s, the scholarly consensus eventually solidified against inclusion of Mark 16: 9– 20. In 1965, that began to change [to inclusion].” See Hester, 10. His work provides the most detailed analysis of scholarly positions on this debate to date. ↑

- James Keith Elliot, “The Text and Language of the Endings to Mark’s Gospel,” TZ 27 (1971): 258. ↑

- Bruce Terry, “The Style of the Long Ending of Mark,” March 27, 2003, accessed March 3, 2017, http://bible.ovc.edu/terry/articles/mkendsty.htm. ↑

- Metzger, A Textual Commentary, 104-105. ↑

- Mark L. Strauss, Four Portraits, One Jesus: an Introduction to Jesus and the Gospels (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2007), 194. ↑

- Argument has been made that even if the LE were authentic these can find complete fulfillment in the events of Scripture by the apostles. See Norman Geisler and Thomas Howe, When Critics Ask: A Popular Handbook On Bible Difficulties (Wheaton, IL: Victor Books, 1992), 378. ↑

- Terry. ↑

- Iverson, “Irony in the End,” 4-6. ↑

- Presuppositions in certain key doctrines can bias a scholar towards a particular viewpoint regarding the ending of Mark, viz., one’s view of source criticism and bibliology. See Daniel Wallace in Perspectives, Kindle locations 169-171. ↑

- Iverson, 4. ↑

- Summary of R. H. Lightfoot, The Gospel Message of St. Mark (Oxford: University Press, 1952), 83 in Ibid. ↑

- Iverson writes, “The end of a document was almost always on the inside of the scroll where it was sheltered from damage. In other words, if any portion of Mark’s Gospel were preserved it would likely be the conclusion.” Iverson, 6. ↑

- The scholars mentioned are B. Weiss, P. Feine, F. Blass and W. K. Lowther Clarke. Bruce, “The End of the Second Gospel,” 174. ↑

- Bruce quoting Theodor Zahn, Geschichte Des Neutestamentlichen Kanons (Leipzig, 1892), 931. ↑

- Stein, 80-83; Metzger, A Textual Commentary, 105-106; and Gene Brooks, “The Last Twelve Verses of Mark: A Text Critical Study of Mark 16:9-20,” Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2006, 2. ↑

- Stein 88. ↑

- Iverson, 6-7. ↑

- Ibid., 7. ↑

- Bruce, 170. ↑

- James Lee Magness, “Sense and Absence: Structure and Suspension in the Ending of the Gospel of Mark,” (PhD diss., Emory University, 1984) in Iverson, 7. ↑

- Thomas E. Boomershine and Gilbert L. Bartholomew, “The Narrative Technique of Mark 16:8,” JBL 100 (1981): 213-23 in Ibid. ↑

- Magness in Ibid. ↑

- Bruce, 173. ↑

- Strauss, 193. ↑

- Iverson, 9. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- It is important to note that while Mark may be portraying the women in a negative light, there is implied obedience for the reader. The women were ultimately obedient to the angel’s command to “go, tell His disciples—and Peter” (v. 7). The reader knows they were not entirely unresponsive by virtue of the fact that they are reading Mark’s gospel. ↑

- Bruce, 176. ↑

- Ibid., 177. ↑

- Strauss, 193. ↑

- Norman Geisler and Thomas Howe, When Critics Ask (Wheaton, IL: Victor Books, 1992), 378. ↑

- Perspectives, Kindle locations 3367-3372. ↑

- Gene Brooks, “The Last Twelve Verses of Mark: A Text Critical Study of Mark 16:9-20” (Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2006), 8-10. ↑

- Maurice A. Robinson in Perspectives, Kindle locations 1565-1566. ↑

- Hester holds a view that the Longer Ending is canonical despite not being written by Mark. ↑

- Hester argues that Metzger later changed his view in favor of the canonicity of the LE despite its non-Markan authorship. See Hester, 87. ↑

- Porter and McDonald strongly hold the position that the original ending was lost. Hester, 82. ↑

Bibliography

Aland, Kurt & Barbara. Text of the New Testament: an Introduction to the Critical Editions and the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, Revised and Enlarged. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989.

Archer Jr., Gleason. A Survey of Old Testament Introduction. 3rd ed. Chicago: Moody Press, 1994.

Boomershine, Thomas E., and Gilbert L. Bartholomew. “The Narrative Technique of Mark 16: 8.” JBL 100 (1981): 213-23.

Bratcher, Robert G. & Eugene A. Nida. A Handbook On the Gospel of Mark. UBS Handbooks; Helps for Translators Series. New York, NY: United Bible Societies, 1993.

Brooks, Gene. “The Last Twelve Verses of Mark: A Text Critical Study of Mark 16:9-20.” Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2006.

Bruce, F.F. “The End of the Second Gospel.” The Evangelical Quarterly 17 (1945): 169–181.

Elliot, James Keith. “The Text and Language of the Endings to Mark’s Gospel.” TZ 27 (1971): 258-62.

Evans, Craig A. Mark 8:27-16:20, Volume 34b (Word Biblical Commentary). Revised ed. Edited by Bruce M. Metzger, David Allen Hubbard, and Glenn W. Barker. Chicago: Zondervan, 2015.

———, and Stanley E. Porter Jr., eds. Dictionary of New Testament Background. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2000.

Farmer, William R. The Last Twelve Verses of Mark. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1974.

Geisler, Norman, and Thomas Howe. When Critics Ask: A Popular Handbook On Bible Difficulties. Wheaton, IL: Victor Books, 1992.

———, and William E. Nix. A General Introduction to the Bible. Rev. ed. Chicago: Moody Publishers, 1986.

Harris, J. Rendel. Side-Lights On New Testament Research. London: James Clarke & Co., 1908.

Hester, David W. Does Mark 16:9-20 Belong in the New Testament? Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2015.

Holmes, Michael W. The Many Endings of the Gospel of Mark. BRev, 17, no. 4 (2001): 19.

Iverson, Kelly R. “Irony in the End: A Textual and Literary Analysis of Mark 16:8.” The Biblical Studies Foundation, May 2001.

Köstenberger, Andreas J., and Michael J. Kruger. The Heresy of Orthodoxy: How Contemporary Culture’s Fascination with Diversity Has Reshaped Our Understanding of Early Christianity. Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway, 2010.

Lightfoot, R. H. The Gospel Message of St. Mark. Oxford: University Press, 1952.

McKnight, Scot, ed. Guides to New Testament Exegesis. Vol. 1, Introducing New Testament Interpretation. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 1989.

Magness, James Lee. “Sense and Absence: Structure and Suspension in the Ending of the Gospel of Mark.” PhD diss., Emory University, 1984.

Metzger, Bruce M. A Textual Commentary On the Greek New Testament. 2nd ed. London; New York: United Bible Societies, 1994.

———. The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University, 1992.

Nineham, D. E. The Gospel of St Mark. London: Penguin Books, 1963.

Petersen, Norman R. “When Is the End Not the End? Literary Reflections On the Ending of Mark’s Narrative.” Int 34, no. 2 (1980): 151-66.

Robertson, A. T. Studies in Mark’s Gospel. New York: Macmillan, 1919.

Robinson, Maurice, Darrell L. Bock, Keith Elliott, and Daniel Wallace. Perspectives On the Ending of Mark: Four Views. Edited by David Alan Black. Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2008.

Schaff, Philip, and Henry Wace, eds. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers. Christian Literature Company: New York, 1890.

Stein, Robert H. “The Ending of Mark.” Bulletin for Biblical Research 18, no. 1 (2008): 79-98.

Strauss, Mark L. Four Portraits, One Jesus: an Introduction to Jesus and the Gospels. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2007.

Taylor, Vincent, ed. The Gospel According to St Mark. 2nd ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1966.

Terry, Bruce. “The Style of the Long Ending of Mark.” Last modified March 27, 2003. Accessed March 3, 2017. http://bible.ovc.edu/terry/articles/mkendsty.htm.

Zahn, Theodor. Geschichte Des Neutestamentlichen Kanons. Leipzig, 1892.