Which Apologetic Approach is Correct?

By Shawn Nelson

September 2019

There is a hot debate in Christianity over which apologetic approach is correct. This paper argues we should use a mixed approach.

This paper was in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the course titled Apologetics and the Art of Persuasion (AP907) taken at Veritas International University in August, 2019.

Copyright © 2019 Shawn Nelson.

Overview

There is a hot debate in Christianity over which apologetic approach is correct. This paper argues we should use a mixed approach (also called Combinationalism and Integrated Apologetics). Eight reasons are given. First, we need different approaches because there are different needs in the church. Second, it is doubtful there is a single correct approach since apologists cannot come up with a single list of apologetic methods. Third, not all systems are logically exhaustive or mutually exclusive. Fourth, many advocates of each major system borrow from different systems. Fifth, the Bible demonstrates many approaches. Sixth, history shows many approaches were used with success. Seventh, we need different approaches because each person is different. Eighth, many of us (including myself) are the product of many different approaches.

Reason 1. We Need Different Apologetics for Different Needs

The first reason we should use a mixed approach is because apologetics is a very broad topic. It is unrealistic to think there is a single approach that covers every area it touches. This can be seen by looking at what apologetics is, and which areas are involved.

Defining Apologetics

Many in the church know apologetics as ‘defending the Christian faith.’ More formally stated, it is “concerned with the defense of the Christian faith against charges of falsehood, inconsistency, or credulity.”[1] While nicely put, this definition quickly broadens. Most agree that there’s a positive side and a negative side to apologetics. On the negative side, apologetics is a defense of Christianity; on the positive side, it is an offense where people are advised to accept it.[2] Once the positive side is added, it now becomes linked with evangelism. “Those who share the gospel must also defend the gospel. People are seeking answers to their questions. Through apologetics we can find those answers.”[3]

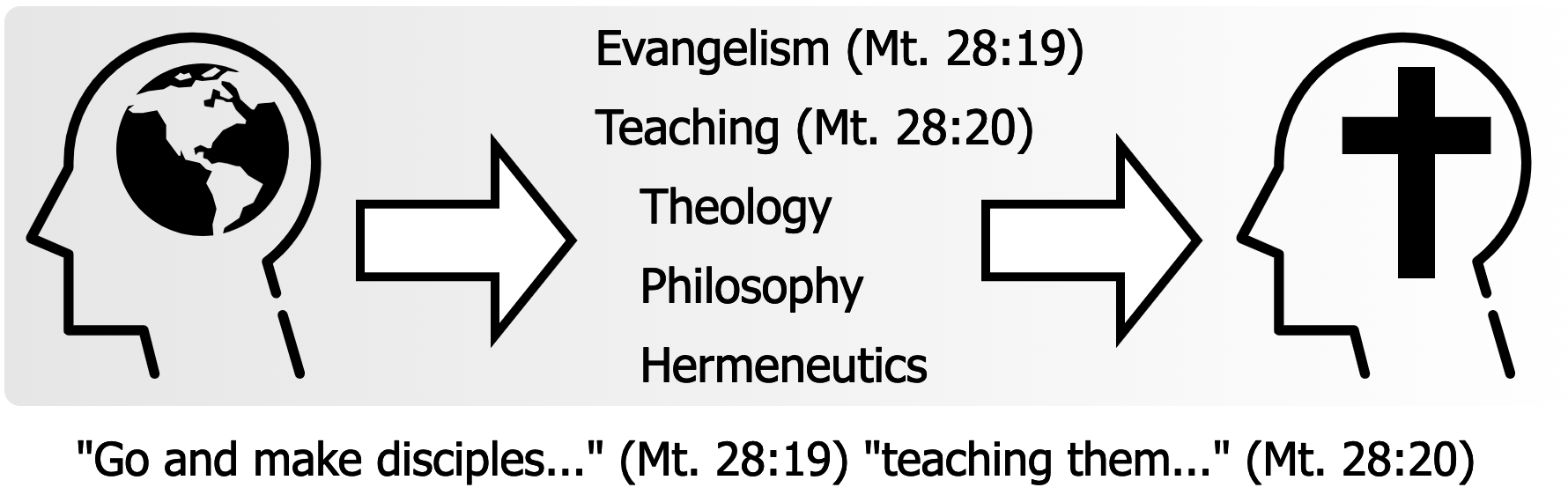

Yet it further broadens. The Great Commission also shows a link between evangelism and teaching. Jesus said, “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you…” (Mt. 28:19, 20, emphasis mine). Christian teaching should completely transform a person’s worldview so that it aligns with the worldview of Christ (Mt. 11:29; Rom. 8:28; 12:2; Eph. 5:26). But for a person to be moved into a new worldview, their old worldview with its reasoning and values must be broken down and the new worldview must be proven to be better. This is also the role of apologetics. This transformation of worldviews will involve theology, philosophy and hermeneutics.

Table 1. Areas touched by apologetics[4]

Since biblical teaching involves learning about God’s nature, nature of man, etc., apologetics is also linked to the study of theology. “The conceptual content of apologetics depends on theology, the goal of which is to systematically and coherently articulate the truth claims of the Bible according to various topics, such as the doctrine of God, salvation and Christ.”[5]

While studying theology, it is impossible to avoid discussions about metaphysics, values (axiology and ethics), knowledge (epistemology) and logic. Therefore, apologetics is also concerned with philosophy. “A Christian-qua-apologist, then, must be a good philosopher (even if not a professional philosopher). This is nonnegotiable and indispensable.”[6] Finally, since Christianity involves interpreting special revelation correctly (the Bible), apologetics also involves hermeneutics. “Apologetics requires skill in reading the Bible aright, since one would not want to defend something not warranted by Scripture…”[7]

Therefore, it is almost a category mistake to ask the question, ‘Which apologetic method is correct?’ Are we talking about evangelism, theology, philosophy or hermeneutics? It is unreasonable to think there is a single method today that is ‘the best’ approach covering all the nuances of what apologetics is. The best approach will change depending on the area being addressed.

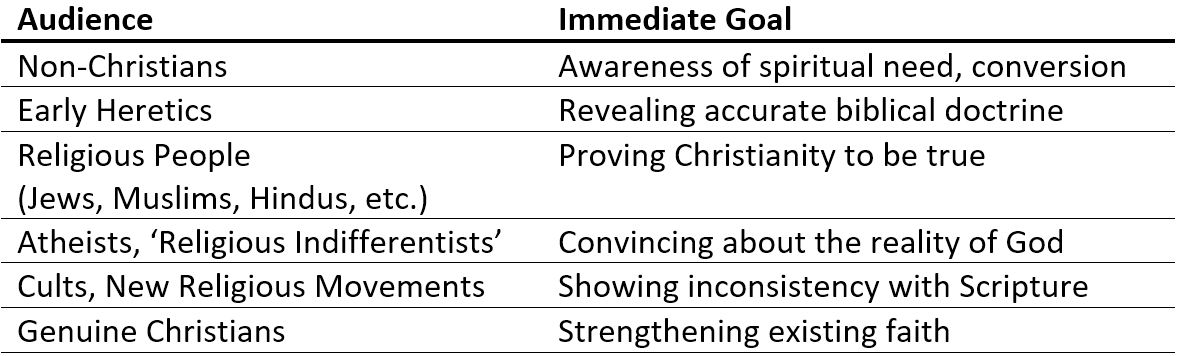

The Audience of Apologetics

Not only does apologetics touch many areas, but it also touches many audiences. See Table 2. The goal of apologetics is not just the persuasion of the unbeliever, but it is just as important for the believer.[8] Defending the faith is needed inside the church too. There are many people who make an initial confession of Christ, but then fall away because of doubt. One example is Charles Templeton (1915-2001), the famous evangelist who turned agnostic. In 1945, he evangelized nightly to crowds of up to thirty thousand. In 1957, he publicly declared himself an agnostic and resigned from the ministry. Why? In his own words:

I had always doubted the Genesis account of creation and could never accept the monstrous evil of an endless hell, but now other doubts were surfacing and, having no one to discuss them with, my personal devotions began to flag.[9]

In short, Templeton had doubts about the soundness of the Christian faith, and with nobody to turn to for answers (at least that is how he felt because he was famous), he lost his foundation. Therefore, people inside the church need apologetics as well.

And it is not just those whose faith is in crisis, but all Christians: “every Christian harbors within himself a secret infidel. At this point apologetics became, to some extent, a dialogue between the believer and the unbeliever in the heart of the Christian himself.”[10]

Therefore, apologetics “is an intellectual discipline that is usually said to serve at least two purposes: (1) to bolster the faith of Christian believers, and (2) to aid in the task of evangelism.”[11]

Table 2. There are different audiences who need apologetics

Which apologetic approach should one take when speaking to a Jew, Muslim or Hindu? Wouldn’t a good place to start be by comparing different religious beliefs and then perhaps discussing evidence for the resurrection of Christ? Which approach is best when talking to a Jehovah’s Witnesses? Wouldn’t it be by looking at how to do proper hermeneutics and showing how the Watchtower Society forces their meaning upon the text? Or what about the best approach for witnessing to ‘religious indifferentists?’ Wouldn’t it be a good idea to start with some kind of moral argument about how America has lost its moral fabric, what a terrible thing this has become, and how there certainly must be some absolute moral underpinning of society that we have neglected (i.e., God)? The approach should vary depending on the audience.

Which apologetic approach should one take when speaking to a Jew, Muslim or Hindu? Wouldn’t a good place to start be by comparing different religious beliefs and then perhaps discussing evidence for the resurrection of Christ? Which approach is best when talking to a Jehovah’s Witnesses? Wouldn’t it be by looking at how to do proper hermeneutics and showing how the Watchtower Society forces their meaning upon the text? Or what about the best approach for witnessing to ‘religious indifferentists?’ Wouldn’t it be a good idea to start with some kind of moral argument about how America has lost its moral fabric, what a terrible thing this has become, and how there certainly must be some absolute moral underpinning of society that we have neglected (i.e., God)? The approach should vary depending on the audience.

Reason 2. Apologists Cannot Agree on the List of Systems

There’s a joke in Judaism that says, “Ask two Jews, get three opinions.” This could easily be said about Christian apologists giving a list of different apologetic systems. Bernard Ramm starts with three.[12] H. Wayne House gives four.[13] Five Views on Apologetics, covers five. Brian Morley goes from five to ten.[14] Phil Fernandes provides seventeen.[15] Interestingly, Fernandes rewrote an earlier book on apologetics because he felt compelled that he and other apologists were completely ignoring some systems:

It is the contention of this author that there has been an oversimplification of the classification of the many different ways to defend the faith. There exists a variety of different ways to defend the faith, and several of these different methodologies are completely ignored. A brief survey of the leading books on apologetic methodologies will confirm this inadequate portrait of apologetic methodologies in books dealing with the subject.[16]

Which apologetic system is the best? It would help by starting with a list of systems. But does such a list even exist? Can we really expect to find the best apologetic approach if there is no starting list where we can compare the different approaches? And why haven’t the major apologists provided such a list? Doesn’t this soften any statement from an apologist that their system is the only way to do apologetics? In the next section, I will combine the list from Fernandes with others from my research to create a list of twenty-eight!

Reason 3. The Systems are not Logically Exhaustive

Not only do many apologists fail to provide a definitive list of systems (previous point) but virtually all recognize there is overlap in the list of systems. Norman Geisler wrote:

It is tempting to make logically exhaustive categories of apologetic systems. Two problems preclude this. First, the category may seem to work but the corresponding category that would logically oppose it is too broad. Second, divergent systems often are lumped into one category.[17]

Despite the warning, we must put together a list to see whether the above quote from Geisler is true. This list reveals Geisler is correct. Here is a comprehensive list made from adding any missing systems to the list provided by Fernandes.[18]

(1) Archaeological Apologetics. Uses evidence from archaeology to defend the accuracy of the Bible. This is a subcategory of Evidentialism.

(2) Classical Apologetics. This system uses two-steps. It argues theism from philosophy first, then Christianity from evidence second. The first step is the same as Rational Apologetics.[19] The second step is the same as Evidentialism. Its strength is that it is comprehensive and thorough. But it can be overwhelming since the first step requires a philosophical mindset.

(3) Combinationalism. This combines different apologetical methods and is also known as Integrated Apologetics. This is the formal name for the method being argued in this paper. I prefer the simple name ‘Mixed Approach’ since there is already so much confusion.

(4) Comparative Religious Apologetics. This compares/contrasts Christianity with other religions and belief systems. After refuting others, Christianity is shown to be true. It can be very helpful and relevant for a person to see how Christianity fits with other beliefs.

(5) Cultural Apologetics. This defends Christianity by showing its positive effects on culture, as well as adverse effects when departing from the Christian worldview.

(6) Cumulative Case Apologetics. Christianity is shown to be more probable by combining different arguments for God. This is consistent with human reasoning. With limited access to data, people must usually infer the best explanation with limited data.[20] This is like Combinationalism but stays within one method of apologetics (like Rational Apologetics).[21]

(7) Dialogical Apologetics. This says the method used depends on the person being witnessed to. It reduces to Combinationalism or Integrated Apologetics.

(8) Dogmatic Presuppositionalism. This is Gordon Clark’s early view.[22] He once held that we must presuppose the Triune God as well as laws of non-contradiction. Only what can be deduced from this is certain. While this attempts to add much needed clarity to presuppositionalism, it is still difficult to distinguish differences with other presuppositional views at times. Also, its founder, Gordon Clark, abandoned this for Scripturalism.

(9) Evidentialism. This is like Classical Apologetics, but without the first step. It stresses rational, historical, archaeological, prophetic and experiential evidence to show Christianity is true. This is a good approach for the modern, scientific world which values inductive reasoning from evidence.

(10) Experientialism. This is the view that experience is the only thing needed. Some are drawn to this approach because Christianity is something a person should experience. However, the challenge with this approach is that experience is too subjective (i.e., there are people of other religions who also claim to have experiences).

(11) Fideism. This system gets its name from the Latin word for ‘faith.’ It says we cannot ultimately prove Christianity. Instead, we must believe it through ‘leap of faith.’ This rightly emphasizes the importance of faith. But it is the weakest positional biblically.[23] Critics also say it is too subjective and does not provide any certainty.

(12) Historical Apologetics. This really should be listed as a branch of Evidentialism. But some people do mention it by name, so it deserves a separate entry in this list. With this, the starting point for defending Christianity is the historicity of the New Testament documents and can include archaeological confirmation of biblical events.

(13) Legal Apologetics. This approach argues for Christ’s resurrection by using legal standards of weighing evidence. Simon Greenleaf and John Warwick Montgomery are examples. It is also a subcategory of Evidentialism but is referred to by name, earning it a place in this list.

(14) Moral Apologetics. Argues for an absolute moral lawgiver (God) from the existence of moral laws. This is a subcategory of Rational Apologetics.

(15) Narrative Apologetics. This creative approach defends Christianity through the telling of fictional stories. John Bunyan, C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien are examples. It appeals to a person’s imagination instead of reason, which Jesus often did with his parables. While it can be a good start, at some point other approaches must be used (emphasizing the need again for a mixed approach).

(16) Paranormal Apologetics. This explains modern paranormal events like UFOs, abductions and haunted houses from a biblical perspective. While arguably a bit bizarre, there is a need to address the growing number of people who are fascinated with this topic with answers from a Christian perspective.

(17) Pragmatism. We should accept what works. Since Christianity is true, it works, and will produce the best life we can have. There is a loose connection here with Experientialism and even Presuppositionalism.

(18) Prophetic Fulfillment. This argues Christianity from fulfilled prophecy. It is also a subcategory of Evidentialism.

(19) Presuppositionalism. In general, this view opposes Evidentialism. It says that our reason is too damaged from the Fall. It also opposes Rational Apologetics by saying all formal proofs for God are invalid. However, of all competing explanations for reality, Christianity alone is coherent. A person must presuppose Christianity in order to argue against it. Therefore, Christianity is true. Note there are more narrow flavors elsewhere in this list: Dogmatic Presuppositionalism and Transcendental Presuppositionalism.

(20) Psychological Apologetics. Argues Christianity from the psychological make-up of man. The Bible’s description of man is the most accurate one we have. Therefore, Christianity is true.

(21) Rational Apologetics. This offers formal proofs for God from reason. It often uses cosmological, teleological, moral and ontological arguments. It is typically lumped with Evidentialism.

(22) Reformed Epistemology. This view rejects Evidentialism and Rational Apologetics by arguing we cannot know anything for certain. However, it argues that people already have an immediate ‘sense of divinity’ or sensus divinitatis). Coming from the Reformers, it sees God’s sovereignty playing an important part in a person coming to faith.

(23) Scientific Apologetics. This would include ministries like Institute for Creation Research, Answers in Genesis, Reasons to Believe and BioLogos. These argue for God while emphasizing a young-earth, old-earth or creation-evolution understanding of science and the Bible.

(24) Scripturalism. This is the late view of Gordon Clark (his earlier view was Dogmatic Presuppositionalism).[24] He argued later in life that truth can only be found in the Bible. No truth comes through the senses.

(25) Testimonial Apologetics. This says the best apologetic is simply to show how Christianity can change a person’s life. A person simply needs to give their own, unique, personal testimony. However, other religions can use this too.

(26) Transcendental Presuppositionalism. The philosopher Cornelius Van Til believed we cannot argue to God but only from God.[25] This strict view said we cannot even test our presuppositions.

(27) Veridicalism. This view comes from Mark Hanna, a teacher at Veritas International University (where this paper is being submitted). Hanna argues that givens are known intuitively and can be corroborated. Since God is a universal given, God can be corroborated.[26]

(28) Verificationalism. Francis Shaeffer had a view like presuppositionalism. He argued that presuppositions act like hypotheses that can be tested. This contrasts with Transcendental Presuppositionalism which argued they cannot be tested.

This list is overwhelming. But with it, it is easy to see that there is much overlap. For example, Historical Apologetics (12), Prophetic Fulfillment (18) and Archaeological Apologetics (1) are considered subcategories of Evidentialism (9). Both Evidentialism (9) and Rational Apologetics (21) together make up Classical Apologetics (2). Since there is overlap, we cannot help but follow different approaches.

Reason 4. Not All Apologists Stay in their Own Camp

Some apologists change camps. There is the curious case of the brilliant philosopher Gordon Clark who switched from Dogmatic Presuppositionalism (8) to Scripturalism (24) in the list above. This is interesting to me because both of his views are extremely narrow, exclusivistic views. If the likes of Clark switched his position, should we be so dogmatic about an exclusivistic view? I argue that we should not.

There are also many apologists who openly embrace different systems. For example, Norman Geisler is a champion of Classical Apologetics (2). Yet he also is known for his Cultural Apologetics (5) and Comparative Religious Apologetics (4).[27] Furthermore, he co-authored a book titled Conversational Apologetics, which is basically Dialogical Apologetics (7). He is no exception. I like the comment from William Lane Craig in Five Views on Apologetics:

Pity our poor editor! Ideally he would like to find a wild-eyed fideist on one end of the spectrum and a hard-nosed theological rationalist on the other. Instead, he winds up with [Gary Habermas] a presuppositionalist who argues like an evidentialist and [himself, William Lane Craig] an evidentialist who endorses belief in Christian theism on the basis of the testimony of the Holy Spirit apart from evidence![28]

What Craig is saying is that neither he, nor Habermas, exactly ‘fit the mold’ of the camps they represent in the book. There seems to be a growing trend that the divisions between the systems are not as hard cut as they used to be. In fact, what we’re seeing is a convergence of views today:

Despite the differences… all will agree with Bill Craig’s comment that in the book we “are seeing…a remarkable convergence of views, which is cause for rejoicing” (p. 317). When I first encountered the question of apologetic methodology almost two decades ago, the debate was often heated and the various approaches starkly polarized… I think this volume, however, represents a growing consensus that the various apologetic methods are not as polarized as they once seemed.[29]

I think this is a good trend. And it illustrates the need for a mixed approach when doing apologetics.

Reason 5. The Bible Demonstrates Many Approaches

This is perhaps the most important part of this paper. Because if the Bible can show us there is a single apologetic method that should be used, then we have answered the question as to which is the best apologetic. However, when we survey the Bible, we see many kinds of approaches being used instead.

Apologetics in the Old Testament

Moses. When God called Moses to deliver his people, Moses answered, “What if they do not believe me or listen to me and say, ‘The Lord did not appear to you’?” (Ex. 4:1) At this, God gave Moses a series of miracles that he could perform to convince the people (the staff becoming a snake, his hand becoming leprous and water becoming blood). The purpose of these miracles was “so that they may believe that the Lord… has appeared to you.” (Ex. 4:5) God would continue to use miracles to convince Pharaoh that Yahweh was the only true God, that he indeed had called Moses, and that he needed to let his people go.

Elijah. The miracle of the fire coming down from heaven and consuming Elijah’s sacrifice was intended to convince the people that Yahweh alone was God, and that Baal was a false god (1 Ki. 18). It was successful! Four hundred prophets of Baal were killed because the people were convinced from the evidence of the miracle (v. 40).

Prophetic confirmation. The Old Testament commands the use of a posteriori reasoning for determining whether a prophet is truly speaking on behalf of the Lord.

You may say to yourselves, “How can we know when a message has not been spoken by the Lord?” If what a prophet proclaims in the name of the Lord does not take place or come true, that is a message the Lord has not spoken. That prophet has spoken presumptuously, so do not be alarmed. (Ex. 18:21, 22)

In other words, we are to examine the evidence and reason with our minds to determine whether what a prophet said really came to pass. Since God alone can tell the future (Isa. 46:10), we see prophecy being used an apologetic, viz., evidence for convincing the people of the reality of God. In contrast, the false prophets cannot accurately prophesy, and this is evidence they are false (Isa. 41:23).

The Israelite nation. The whole thrust of the Old Testament is that God is a God who intervened in the affairs of mankind. Instead of abandoning or annihilating his fallen creation, he intervened in history and began to reveal his plan of salvation beginning with real people like Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. He raised up a nation through a salvation event called the Exodus. He further guided this nation in history by maturing it into a kingdom. He delivered the people into captivity as discipline but through another salvation event, brought them back into the land of promise. These events are reported as real events in history and are given as evidence for a loving, personal (theistic) God.

Conclusion. The Old Testament seems to validate the use of appealing to evidence and fulfilled prophecy as a means for convincing people about the truth of God. While the Old Testament might not try to prove God the way modern approaches do today, it does build a positive case for the one true God by arguing against trusting in false gods. The general thrust of the Old Testament is that all people, especially the Israelites, should trust in the Lord because he has acted inside history to save believers or punish unbelievers. The Old Testament seems to corroborate the use of Evidentialism (9), Prophetic Fulfillment (18) and even Comparative Religious Apologetics (4).

Apologetics of Jesus

Jesus appealed to miracles. Jesus frequently appealed to the miracles that he performed as evidence that he was the promised Messiah (Mt. 11:2-6; Lk. 7:20-23; Jn. 3:2; Jn. 5:36; 6:14; 7:31; 9:16; 9:30-33; 11:42; 11:47,48; 12:37; 15:24). When Nicodemus came to Jesus, he said, “Rabbi, we know that you are a teacher who has come from God. For no one could perform the signs you are doing if God were not with him.” (John 3:2). At one point, Jesus flatly told his followers, “Do not believe me unless I do the works of my Father.” (Jn. 10:37) Jesus pinned his authenticity on the miracle of the resurrection itself:

The Jews then responded to him, “What sign can you show us to prove your authority to do all this?” Jesus answered them, “Destroy this temple, and I will raise it again in three days.” … But the temple he had spoken of was his body. After he was raised from the dead, his disciples recalled what he had said. Then they believed the scripture and the words that Jesus had spoken. (John 2:18, 19, 21, 22)

Jesus appealed to prophecy. Jesus also appealed to fulfilled prophecy as evidence he was the Messiah. Jesus began his public ministry by turning to Isaiah 61:1, 2, reading it, and then saying, “Today this scripture is fulfilled in your hearing.” (Lk. 4:21) When the woman at the well said she knew Messiah was coming, Jesus answered, “I, the one speaking to you—I am he.” (Jn. 4:25, 26) He claimed that the entire volume of Old Testament writings provided evidence for him (Jn. 5:39). Jesus fulfilled so much prophecy that he said this to some of his disciples after his resurrection:

How foolish you are, and how slow to believe all that the prophets have spoken! … And beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, he explained to them what was said in all the Scriptures concerning himself. (Lk. 24:25, 27)

Jesus used logic. Jesus was not just a masterful teacher, but he was also a masterful logician. How did he use logic? Jesus’ favorite mode of argumentation was the a fortiori argument. This kind of argument starts with an accepted conclusion and then argues there is a stronger conclusion that is more obvious. These types of arguments can be found by looking for the ‘how much more’ statements of Jesus. God feeds the birds—how much more will he feed people! (Lk. 12:24-24). God clothes the grass—how much more will he clothe you! (Lk. 12:28) Sheep are important and worthy of rescuing on the Sabbath—but how much more important are people in need on the Sabbath! (Matt. 12:10-13) This reasoning can also be seen in his ‘one greater than’ statements. People (like Queen of Sheeba) listened to Solomon’s wisdom—but now one greater than Solomon is here (i.e., how much more should they listen to him)! (Lk. 11:31) People repented at the preaching of Jonah—but now a prophet greater than Jonah is here (i.e., how much more should they listen to him)! (Lk. 11:32)

Jesus also demonstrated how to traverse logical dilemmas. The Pharisees tried to trap Jesus using a dilemma. They asked, “Is it right to pay the imperial tax to Caesar or not?” (Mt. 22:17) If he answered yes, he would be supporting the opposition. If he answered no, they could rightfully try him for treason. Instead of yes or no, he went ‘between the horns’ by presenting a third option. Coins have Caesar’s image so “give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s.” People have God’s image so give back “to God what is God’s.” (Mt. 22:21) He was also able to use dilemmas to stump his opponents. One instance is when he asked his opponents whether John’s baptism was “from heaven or from men?” (Lk. 20:3).

They discussed it among themselves and said, “If we say, ‘From heaven,’ he will ask, ‘Why didn’t you believe him?’ But if we say, ‘Of human origin,’ all the people will stone us, because they are persuaded that John was a prophet.” So they answered, “We don’t know where it was from.” Jesus said, “Neither will I tell you by what authority I am doing these things.” (Lk 20:5-8)

Jesus was so good at arguing that towards the end of the Gospel it says, “No one could say a word in reply, and from that day on no one dared to ask him any more questions.” (Mt. 22:46; Mk. 12:34; Lk. 20:40).

Jesus appealed to the Bible as history. Jesus based some of his arguments on historical biblical events. People should not get divorced because God made the real first couple, Adam and Eve, “one flesh.” (Mt. 19:4-6). He spoke about Noah and the Flood (Mt. 24:39; Lk. 17:27), Abraham (Lk. 3:34; Jn. 8:56), Moses (Jn. 6:32), the Davidic Kingdom (Mt. 22:43), Solomon (Mt. 6:29), even events like Jonah and the Fish (Matt. 12:40) and the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah (Lk. 17:29).

Conclusion. Jesus’ use of logic adds good weight to Rational Apologetics (21). His appeal to evidence (e.g., the resurrection) and fulfilled prophecy validate Evidentialism (9). Both confirm Classical Apologetics (2) since it is made up of both. He also seemed to confirm Historical Apologetics (12) by appealing to the Bible as history.

Apologetics of the Gospel writers

Each of the four Gospel writers seem to have a different audience in mind, and each used a different strategy to reach them.

Matthew. Matthew, for example, was primarily writing to convince Jewish people that Jesus was the promised Messiah. Therefore, he centers his argument for Jesus around fulfilled prophecy. In his Gospel, we repeatedly find the phrase “that it might be fulfilled” (Mt. 1:22; 2:15, 17, 23; 4:14, 15; 8:17; 12:16-18; 21:4; 26:54, 56; 27:35).

Luke. All four Gospels claim to be accurate eyewitness testimony of the life, crucifixion, burial and resurrection of Jesus Christ. But Luke specifically states that he “carefully investigated everything from the beginning” (Lk. 1:3) to ensure that the details in his gospel were factual. It was very important to him that his readers “know the certainty of the things you have been taught” (Lk. 1:4). Therefore, he makes an appeal to the historicity of his own gospel account.

John. John appealed to miracles as proof that Jesus was Messiah. “Jesus performed many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not recorded in this book.” (Jn. 20:30) He even structured his gospel around seven specific miracles. The purpose for this was so “that you may believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name.” (Jn. 20:31)

Conclusion. All the Gospels, in pointing to the resurrection bring support for Evidentialism (9). Matthew offers good support for Prophetic Fulfillment (18). Luke’s emphasis in documented reliability offers support for Historical Apologetics (12).[30]

Apologetics in Acts

We see persuasive arguments being given throughout the book of Acts. When God used Peter to bring the Gospel to the Jewish people, he did so by presenting an argument for Christ being the Messiah from fulfilled prophecy (Acts 2:25-28; 34, 35). His persuasive argument resulted in three-thousand people being saved (v. 41). We also find Paul reasoning with people on his evangelistic missionary journeys. We frequently encounter statements like,

Then Paul, as his custom was, went in to them, and for three Sabbaths reasoned with them from the Scriptures, explaining and demonstrating that the Christ had to suffer and rise again from the dead [from the Old Testament], and saying, “This Jesus whom I preach to you is the Christ.” (Acts 17:2, 3)

We find him reasoning again in Acts 17:17, 18:4, 18:19 and 24:25. How did he reason? It seemed that he started where people were at (1 Cor. 9:20-22). When approaching the heathen, he started with nature (Acts 14); when approaching Jews, he started with the Old Testament (Acts 17a); when approaching Greeks he started with reason (Acts 17b); when approaching Christians he started with Jesus’ words (Acts 20).[31]

Conclusion. The apostles in Acts seem to emphasize the need to present good arguments for Jesus. This is a blow to Fideism (11). We see strong appeal to evidence and prophecy. This supports Evidentialism (9) and Historical Apologetics (12). Paul specifically varied his approach depending on the audience which is a clear case of Combinationalism (3) or Cumulative Case Apologetics (6).

Apologetics in the epistles

Paul’s epistles. Paul was so committed to the rational defense of the faith that he summarized his ministry in these words: “I am put here for the defense [apologia] of the gospel.” (Phil. 1:16) He would eventually be imprisoned for “the confirmation of the gospel” (Phil. 1:7). He wrote all Christians bear a responsibility to rationally defend the faith with these words:

Walk in wisdom toward those who are outside [i.e., non-Christians], redeeming the time. Let your speech always be with grace, seasoned with salt, that you may know how you ought to answer each one [i.e., apologetics]. (Colossians 4:5, 6)

Peter’s epistles. Peter also confirmed the use of apologetics when he said we should always be “prepared to make a defense [apologia] to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you…” Peter appealed to the historicity of the gospel account when he says, “we did not follow cleverly devised stories when we told you about the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ in power, but we were eyewitnesses of his majesty.” (2 Pt. 1:16) He also appealed to the events of Noah’s Flood and the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah as evidence of coming judgment (2 Pet. 2:5-9).

Jude’s letter. Jude wanted to talk about salvation in his short letter. But instead, he “found it necessary to write appealing to you to contend for the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3, emphasis mine). For these reasons, every Christian should be involved in apologetics at some capacity.

Conclusion. The New Testament writers seem to present a unanimous case that we should be ready and willing to rationally defend Christianity when opportunities present itself. There are appeals made to the resurrection, other miracles in the life of Christ, fulfilled prophecy and even consistency (congruency) with Old Testament revelation. The biblical passages above demonstrate Classical Apologetics (2), Combinationalism (3), Cumulative Case Apologetics (6), Evidentialism (9), Historical Apologetics (12), Legal Apologetics (13) and Prophetic Fulfillment (18). We should therefore follow a mixed approach today.

Reason 6. History Shows Many Approaches Were Used with Success

What about apologetics in the history of the church? Again, when we survey different periods of history, we find that many different apologetic approaches were used.

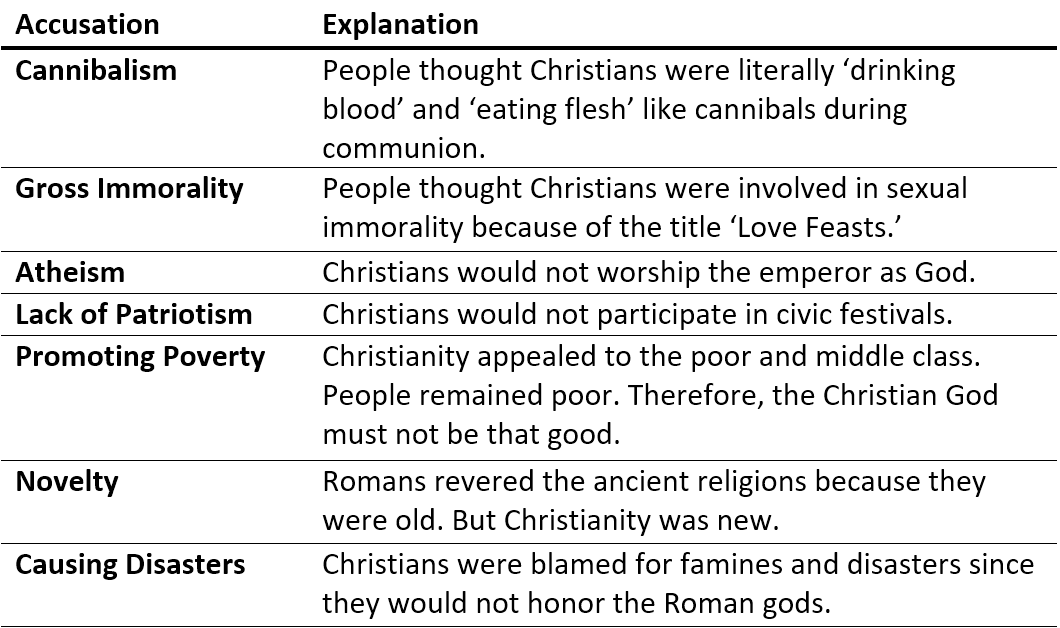

Apologetics in the Church – Before Modernism

The early post-biblical church was concerned about defending themselves against the charges of the state. The charges included cannibalism, gross immorality, atheism, lack of patriotism, poverty, novelty and causing disasters (see Table 3). “The earliest apologists were primarily concerned with obtaining civil toleration for the Christian community—to prove that Christians were not malefactors deserving the death penalty.”[32]

Table 3. Early accusations against Christians[33]

In short, the emphasis of the early church was on piety and godly living, not with “attempting to demonstrate the credibility of the Christian faith.”[34]

In short, the emphasis of the early church was on piety and godly living, not with “attempting to demonstrate the credibility of the Christian faith.”[34]

Change in 2nd century. There began to be a real need to defend Christianity with the rise of heresies. The 2nd century brought a mature Gnosticism with a belief in a pleroma of gods, a Jesus that was not fully human, and a salvation that was by means of secret knowledge. The 3rd century brought Arianism which was a denial of the deity of Christ. The 4th century brought Pelagianism which denied original sin. Meanwhile, the church also felt the need to defend itself from formal religions like Judaism, Manicheanism and from attacks by secular philosophers. All of these needed a response by the Church.

We see the rise of the apologists beginning with the 2nd century AD. Formal apologetic works appeared from Justin Martyr (AD 100-165), Clement of Alexandria (AD 150-215), Tertullian (AD 155-220) and Origen (AD 184-253). But like today, there was no real consensus as to how to ‘do apologetics.’ There were disagreements. There was no clear theory of the relationship between reason and revelation.[35] There was some debate over the role of philosophy (e.g., Clement and Origen were for philosophy, Tertullian was against).

Middle Ages. Athanasius (AD 296-373) and Augustine (AD 354-430) were the first to look at reason and faith. They “offer an impressive philosophical rationale for the faith. They probe the inner relationships between seeing and believing, between reason and authority.”[36] Al-Kindi delivered a much-needed polemic against Islam around AD 873. The great philosopher Anslem (AD 1033-1109) argued a rational proof for God. Muslim philosophers like Averroes (AD 1126-1198) were developing Muslim apologetics for winning converts to Islam. Men like Thomas Aquinas (AD 1225-1275) rose to the apologetic challenge and provided arguably the best defense of the Christian faith the church has seen.

Conclusion. The early part of church history is where we get the phrase ‘classical apologetics.’ These early apologists were arguing God using philosophy as well as from evidence. So clearly there is much support for Classical Apologetics (2), Evidentialism (9), and any method that is derived from Evidentialism. But there was also much emphasis on refuting other religious systems, and so there can be much support for Comparative Religious Apologetics (4) from this time.

Apologetics in the Church – After Modernism

The Age of Enlightenment brought a massive shift in apologetics. This is best summed up by Dulles:

For the medieval theologians, apologetics was a contest among the three great monotheistic faiths—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—all of which appealed to historical revelation. But after the Renaissance, apologetics had to address thinkers who rejected revelation entirely and who in some cases denied the existence or knowability of God. For the first time in history, orthodox Christians felt constrained to prove the existence of God and the possibility and fact of revelation.[37]

David Hume (1711-1776) brought a formal argument against the possibility of miracles. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) said there was a limit to what we can know about reality (we cannot know things in themselves, only things as they seem to me). The positivists brought scientism, which is the notion that only things which can be empirically tested qualify as truth. Charles Darwin (1809-1882) proposed the theory that life could evolve on its own, without the need for a creator.

The response from many in the church was to salvage what they could from the Christian gospel message. The deists ‘desupernaturalized’ the Bible, including the resurrection, and tried to keep its moral fabric. Yet attacks on the Christian faith continued. Julius Wellhausen (1844-1918) proposed a ‘documentary hypothesis’ which says that the first five books of the Bible were not actually written by Moses. Many liberal scholars went on three ‘quests to discover the historical Jesus.’ Rudolf Bultmann (1884-1976), continued to demythologize the text to make Christianity more appealing to people. The result is a growing liberalism today, where many feel the gospel message is not an actual event in history that can be appealed to, but an idea. The best we can do is turn inward to some ‘sense of religious feeling.’[38]

The net of all of this is that this is the context in which the Christian apologist finds themselves today. Christianity is now an overwhelming task in the 21st century. It involves many disciplines and is very broad in scope. “Modern apologists must contend for the faith in the face of a philosophical naturalism and a cleverly selective skepticism that earlier apologists did not confront.”[39] There is also sharp disagreement post-Kant (when most people lost confidence in our ability to know reality) about what is a valid epistemological methodology.

Enter presuppositional approaches. This is the context that has given rise to the presuppositional approaches. The presuppositional systems remain skeptical of our ability to know or understand reality. They reject the use of general revelation. I personally am not convinced that these systems are the best approaches (based on the biblical data, and the emphasis of the early church pre-Kant). But nonetheless, if I were working with an unbeliever who held some Kantian worldview, I think it might be a good place to start. For example, I could argue that, without proving Christianity with evidence, but just given Christianity, it alone is the worldview that is the most coherent. In fact, one must presuppose Christianity (e.g., that there is objective meaning, etc.) in order to argue against it. This leads me to the next point, that we should try to reach each person where they are at.

Reason 7. Each Person is Different

One of the key takeaways from Winsome Persuasion: Christian Influence in a Post-Christian World is that each person is different.[40] Each person has a framework of values through which they see the world. The goal of an effective persuader should be to find common values through which to build a bridge into the lives of the hearer. Some may value reason and science; others may be skeptical of our ability to know reality. How would we witness to a person from each camp? Should we try to persuade somebody who is a rationalist that empiricism is valid—before we even attempt to bring them to Christ? How would we witness to an Immanuel Kant? Or a Charles Darwin? I suggest that different approaches should be taken, depending on the person and the situation. With this in mind, we can make use of all the methods—even if we don’t necessarily believe they are ‘the best.’

Reason 8. My Own Personal Experience

I have formally studied classical apologetics now for seven years in seminary. I could have written a paper about how the classical view is the only view that makes sense.[41] However, L. Russ Bush wrote, “Did we come to know Christ according to the methodology by which we do our apologetics?”[42] For me, I would have to say, no!

What drew me to God? My story of coming to faith is a mix of different apologetic views. I remember having an immediate awareness of the presence of God, like Reformed Epistemology teaches. But I also was starting to become aware that there must be a God who exists, because how could this universe just have happened from nothing? This is much like the cosmological arguments found in Rational Apologetics. When I accepted the Lord into my heart, I felt like the Lord was present with me from that day on, like Experientialism teaches. About six months into my walk, I had a crisis of faith, where I felt as though I could fall away from the faith because it did not seem possible to prove beyond all doubt that Christianity was true. I decided to accept it as most reasonable even though I had doubts about whether it was provable. There are elements here that sound like Fideism and Presuppositionalism. As I continued to grow, I encountered books like Josh McDowell’s Evidence That Demands a Verdict (Evidentialism) and began reading material from Institute for Creation Research (Scientific Apologetics).

Which apologetic was ‘correct’ for me? I would have to say that God has used many different approaches to help grow me and keep me convinced Christianity is true all these years. I am very much the product of a mixed apologetic approach.

Can We Apologists Tone Down the Rhetoric?

People like me who want to be involved in apologetics in the local church feel they are ‘swimming against the stream’ of popular Christianity. “In the minds of many Christians today the term ‘apologetics’ carries unpleasant connotations.”[43] Here’s why.

Churches tend to think of ‘those who are into apologetics’ as people who like to cause divisions. They usually have very strong opinions about minor, secondary Christian issues. These are issues like how old is the age of the earth, which is the proper view of the days of creation, God’s sovereignty vs. man’s responsibility, whether the charismatic spiritual gifts are valid for today, which type of church government is correct, the role of women in the church, etc.[44] Church leaders often feel that apologists and theologians, especially those who pursue academic studies in seminaries, are notorious for ‘majoring in the minors’ or ‘making mountains out of mole hills.’ Moreover, many apologists are not gentle about expressing their views. Instead, they are often harsh and insulting to each other. This can be seen in many debates between prominent leaders of any view in Christian academia. As a result, “the word apologetics is often used today in a derogatory way to mean a biased and belligerent advocacy of an indefensible position.”[45]

Need for humility. There is a genuine need for humility in the church today, especially in the area of intellectual pursuits like apologetics and theology. Put plainly, there is a sense that those who are into apologetics—and the related disciplines of theology, philosophy, etc.—are arrogant and prideful. Ron Rhodes, who was co-host of the popular radio program The Bible Answer Man said,

Believe me, I’ve been involved in this business for decades. And I’ve got to tell you something. There’s more pride per square inch in the apologetics community than anywhere else on the planet. And it shouldn’t be that way.[46]

This is consistent with Paul’s testimony in 1 Corinthians 8:1 that knowledge tends to puff a person up. We can add the advice from John Frame:

Apologists, therefore, must resist temptations to contentiousness or arrogance. They must avoid the feeling that they are entering into a contest to prove themselves to be righter or smarter than the inquirers with whom they deal. I believe that kind of pride is a besetting sin of many apologists, and we need to deal with it.[47]

To be persuasive people, we must present arguments that are not just intellectually sound, but we must also have deep humility, because we are working with people who disagree with us.[48] Being humble means we check ourselves for prejudice and show respect and goodwill towards opponents.[49] This is consistent with the second half of 1 Peter 3:15 which says, “…Always be prepared to give an answer [apologia] to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have. But do this with gentleness and respect…” (emphasis mine).

Conclusion

The point of this paper was to show that there is no single apologetic approach today which is ‘the correct’ one. This was shown in eight ways. First, apologetics is a broad topic that covers many areas. Different methods need to be taken because there are audiences needing apologetics in the church. Second, apologists cannot seem to agree on the list of apologetic systems. Therefore, it is questionable whether there is a single ‘correct’ way. Third, the systems that are given by apologists are not logically exhaustive—many of them overlap. Fourth, many famous apologists borrow from more than one system. Fifth, the Bible demonstrates many approaches. Sixth, history shows many approaches were used with success. Seventh, since each person has a different set of philosophical values, different methods should be used to reach them with the Gospel. And eight, my own personal story illustrates (to me anyway) that God can and does use different systems throughout a person’s walk to keep them grounded and secure in the faith. Finally, an appeal was made to tone down the rhetoric between apologists since it is a discipline that has a negative stigma today.

Footnotes

- Steven B. Cowan, ed., Five Views on Apologetics (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Academic, 2000), 8. ↑

- H. Wayne House, The Evangelical Dictionary of World Religions (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2018), 27. I should add that another word to describe this positive aspect of apologetics is polemics. ↑

- Phil Fernandes, The Fernandes Guide to Apologetic Methodologies (Bremerton, WA: Institute of Biblical Defense, 2016), Kindle loc. 83. ↑

- Graphic includes icons made by Freepik, https://www.flaticon.com/authors/freepik. ↑

- Groothuis said, “Apologetics is linked to theology, philosophy and evangelism, but it is not reducible to any one of these disciplines.” See Douglas Groothuis, Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith (Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2011), 27. ↑

- Groothuis, Christian Apologetics, 27 ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- For an opposing view, Feinberg said he thought apologetics was for the persuasion of the unbeliever and not the establishment of the Christian truth. See Cowan, Five Views on Apologetics, 345. ↑

- Charles Templeton, Farewell to God (Toronto, ON: McClelland & Stewart, 1996), 6. ↑

- Avery Dulles, A History of Apologetics (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1999), Kindle loc. 278-9. ↑

- Cowan, Five Views on Apologetics, 8. ↑

- Bernard Ramm, Varieties of Christian Apologetics (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1979), 15-17. ↑

- H. Wayne House in Joseph M. Holden, ed., The Harvest Handbook of Apologetics (Eugene, OR: Harvest House Publishers, 2019), 38. ↑

- Brian K. Morley, Mapping Apologetics (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015), 28. ↑

- Fernandes, The Fernandes Guide to Apologetic Methodologies, Kindle loc. 6569-6674. ↑

- Ibid., 47. ↑

- Norman L. Geisler, Baker Encyclopedia of Christian Apologetics (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Reference Library, 1999), 41. ↑

- Fernandes, Kindle loc. 6569-6674. ↑

- I have broken convention and purposely capitalized references to other systems in the list for clarity. ↑

- This is called an abduction in logic. ↑

- Fernandes, Kindle loc. 6631-7. ↑

- Ibid., Kindle loc. 6603-11. ↑

- The Bible seems to be clear that we are to provide evidence. See Reason 5 below. ↑

- Fernandes, Kindle loc. 6612-6. ↑

- Fernandes, Kindle loc. 6594-6601. ↑

- See Morley, Mapping Apologetics, 20, 21. ↑

- Fernandes, Kindle loc. 6724-6626. ↑

- Cowan, Five Views on Apologetics, 122. ↑

- Cowan, Five Views on Apologetics, 380. ↑

- The central argument in Luke is that Jesus’ trial was illegal. “He was not convicted in a bona fide court. Pilate declares his innocence three times (Lk 23:4, 14, 22), and so does the Roman centurion attending his crucifixion (Lk 23:47).” See Morley, Mapping Apologetics, 28. This touches Legal Apologetics (13). ↑

- Norman L. Geisler, “NT501: Apologetics” (lecture, Veritas International University, Murrieta, CA, May 20, 2013), PowerPoint file 0-ApolforApolsht.oc.ppt. ↑

- Dulles, Kindle loc. 275. ↑

- “Accusations,” Christianity.com, accessed August 30, 2019, https://www.christianity.com/church/church-history/timeline/1-300/accusations-11629581.html. ↑

- Dulles, Kindle loc. 771. ↑

- Ibid., Kindle loc. 955. ↑

- Ibid., Kindle loc. 1779. ↑

- Dulles, Kindle loc. 3627-30. ↑

- This saying was expressed by Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834). ↑

- L. Russ Bush, ed., Classical Readings in Christian Apologetics (Grand Rapids, MI: Academie Books, 1983), xvii-xviii. ↑

- See Tim Muehlhoff and Richard Langer, Winsome Persuasion: Christian Influence in a Post-Christian World (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2017). The entire book is rich with this advice. But see esp. chap. 5. ↑

- My argument would be this: the classical approach alone provides a deductive argument starting from first principles. The Bible rules out fideism and in so doing validates appeal to evidence. However, evidentialism alone is merely an inductive argument which cannot prove anything for certain. Therefore, for certainty, a deductive approach is needed. Hence, the classic approach is ‘the correct’ view. ↑

- Bush, ed., Classical Readings in Christian Apologetics, 385, emphasis mine. ↑

- Dulles, Kindle loc. 260-1. ↑

- For a more exhaustive list, Shawn Nelson, “Important Safety Rails in the Creation Debate,” Nelson.Ink, December 1, 2018, https://nelson.ink/important-safety-rails-in-the-creation-debate/, especially Illustration 2. I show the odds of me finding somebody who agrees on every point as I do in a conservative Christian church is a whopping one in 97 quadrillion! ↑

- Douglas Groothuis, Christian Apologetics, 24. ↑

- Ron Rhodes, “RE505: Contemporary Cults” (lecture, Veritas International University, Murrieta, CA, 2014), lecture 4. ↑

- Cowan, ed., Five Views on Apologetics, 220. ↑

- Muehlhoff and Langer, Winsome Persuasion, Kindle loc. 1397. ↑

- Ibid., Kindle loc. 1410, 1436-44. ↑

Bibliography

Bush, L. Russ, ed. Classical Readings in Christian Apologetics. Grand Rapids, MI: Academie Books, 1983.

Christianity.com. “Accusations.” Accessed August 30, 2019. https://www.christianity.com/church/church-history/timeline/1-300/accusations-11629581.html.

Cowan, Steven B., ed. Five Views on Apologetics. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Academic, 2000.

Dulles, Avery. A History of Apologetics. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1999.

Fernandes, Phil. The Fernandes Guide to Apologetic Methodologies. Bremerton, WA: Institute of Biblical Defense, 2016.

Geisler, Norman L. Baker Encyclopedia of Christian Apologetics. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Reference Library, 1999.

———. “NT501: Apologetics” Lecture, Veritas International University, Murrieta, CA, May 20, 2013, PowerPoint file 0-ApolforApolsht.oc.ppt.

Groothuis, Douglas. Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith. Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2011.

Holden, Joseph M. Ed. The Harvest Handbook of Apologetics. Eugene, OR: Harvest House Publishers, 2019.

House, H. Wayne. The Evangelical Dictionary of World Religions. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2018.

Morley, Brian K. Mapping Apologetics. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015.

Muehlhoff, Tim, and Richard Langer. Winsome Persuasion: Christian Influence in a Post-Christian World. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2017.

Nelson, Shawn. “Important Safety Rails in the Creation Debate.” Nelson.Ink. December 1, 2018. https://nelson.ink/important-safety-rails-in-the-creation-debate/.

Ramm, Bernard. Varieties of Christian Apologetics. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1979.

Rhodes, Ron. “RE505: Contemporary Cults.” Lecture, Veritas International University, Murrieta, CA, 2014, lecture 4.

Templeton, Charles. Farewell to God. Toronto, ON: McClelland & Stewart, 1996.